Rebel writing: ‘Coronavirus will expose the deadly flaws of the corporate food regime’

May 12, 2020

The following piece is written by an XR Scotland rebel, Marco T and republished from Bella Caledonia.

The corporate food regime that dominates global food production is actively undermining our resilience to systemic crises and increasing the risks of pandemic. Coronavirus poses a serious threat to global food security – not because of disruptions to supply or spikes in demand, but because the looming global recession will bring into sharp relief the ways in which global agriculture creates systematic poverty and vulnerability.

The unfamiliar sight of empty supermarket shelves in developed economies such as the UK has raised questions about the threats Covid-19 poses to global food supplies. The food production, processing and distribution sectors are operating in over-drive, lengthening working hours, hiring extra staff and simplifying production to focus on volume of key items. Labour shortages pose a serious threat to fresh produce as flows of seasonal labour are disrupted, but there is already talk of European governments supporting the necessary mass transit via chartered flights of tens of thousands of fruit pickers for the summer harvest.

Food scarcity in the global north seems an unlikely scenario. The global food system has been fine-tuned to provide the global ‘consumer class’ abundant quantities and varieties of food. The corporations and governments which maintain that food regime are well resourced enough to weather the storm. Of course, that is not to say that food insecurity does not exist in developed countries, even in times of economic normality over a million people in the UK are forced to use foodbanks.

Indeed, food insecurity is usually driven by poverty rather than systemic food scarcity. That much is made clear by the ultimate signifier of the deep inequity of our global food system: the fact that today we produce roughly 1.5 times the food needed to feed 7.8 billion people on this planet. And yet, malnourishment is endemic, particularly amongst the world’s peasantry who produce most of the world’s food. In a world where food is more commodity than a means of reproduction, food insecurity is rarely caused by unavailability of food per se, but by an inability to pay.

The corporate food regime:

The systemic inequities of our food system need to be understood in reference to the way in which global agricultural policy has been actively shaped over the past 70 years to benefit the corporations, governments and consumers of the world’s most powerful economies.

Following World War Two, western governments invested heavily in agriculture and under the auspices of the WTO, pushed for a process of trade liberalisation, pitting peasants from the global south against heavily subsidized industrial agricultural from the global north.This ‘dumping’ of agricultural goods led to a decoupling of production costs for western corporations from global prices, and enabled a small number of northern transnational corporations to concentrate power and dominate agricultural markets. By 2008, five corporations controlled 90% of the global grain trade, and today world agriculture is dominated by as few as 10 trans-national corporations such as Cargill, Monsanto and Carrefour across retail, commodities trading, and inputs. This aggressive concentration of power allows companies to pay farmers low prices for output and charge high prices for inputs.

Under the pretence of feeding the world, the green revolution was instrumentalised by American and European governments to create global dependency on capitalist products and markets. Mechanised agriculture, genetically modified crops and export-oriented trade policies were pushed as a miracle cure for impoverished rural economies, when in fact they created a highly efficient system for transferring value from global south communities and ecosystems to the global north. This can be seen in the longer view as another step in the imperial project of maintaining the peripheries of global capital underdeveloped, ensuring a cheap pool of easily exploitable labour and resources.

As land was enclosed, production mechanised and prices driven below subsistence levels, 25% of the world’s peasantry were driven off their land. Indeed, the movement of destitute peasants to urban centres around the global south over the past 70 years probably represents the biggest migration in human history. These displaced rural peoples amassed on the urban periphery, the world’s sprawling shantytowns, favelas and townships. According to the UN at least a billion people live in slums today.

These densely populated settlements, typified by a lack of health services, clean water or sanitation are the ideal place for a virus to spread. Stockpiling food and self-isolation is a luxury that the global precariat, living hand-to-mouth and check-by-jowl, cannot afford. The risk is that food insecurity, contagion, poverty and weak states brew a perfect storm of mortality, where Covid-19 becomes endemic until a vaccine is found.

The corporate food regime has also fundamentally changed what we eat and by undermining the quality of our diets, has left us more susceptible to disease and other shocks. The aggressive growth of fast food and supermarket culture around the world has alienated people from the cultural and social culinary practices traditionally embedded in food consumption. As a result, diets have converged on processed foods with high fat and sugar content, resulting in epidemics of obesity, diabetes and heart disease. These diseases are more prevalent in poorer households and today, those suffering from these conditions are amongst the most vulnerable to Covid-19.

Indeed, intensive capitalist food production is not only reducing our resilience to, but is actually causing epidemic outbreaks. The constant development of new extractive frontiers—be they trawling the deepest seas or burning the remote amazon for soy plantations—is bringing us into dangerously close contact with novel microbes which our immune systems have no defences for. For example, Ebola outbreaks have been shown to be more prevalent in communities in West and Central Africa with high levels of deforestation, as the destruction of the Ebola-carrying bat’s natural habitats drives them to seek refuge in human settlements. The biologist Rob Wallace has argued that industrial animal farming in particular causes a serious threat to global public health. He argues that you “couldn’t design a better system to breed deadly diseases” than overcrowded genetic monocultures of unhealthy animals pumped full of antibiotics.

Globalization is a risky business:

Most smallholders who remained in the countryside were integrated into the corporate food regime, pushed through policy instruments or economic coercion to pursue intensive cash-crop monocultures for global supply chains. This has led to 75% the world’s food crop diversity being lost and soils and aquifers being heavily depleted, and has left smallholders dependent on global markets for their food security.

Through the 80s and 90s the WTO worked to formally shift the locus of food security provision from the state, to the world market. As a result, global south countries on aggregate have slowly but surely become net importers of food where once they were net exporters. Self-sufficiency has been slowly replaced with dependency, and the looming global economic and public health crisis will once again highlight the lethal flaws of this system.

The number of confirmed global infections passes 2 million, much of the world’s population is under lock-down and full economic activity may not be able to resume until a vaccine becomes available, which could take anywhere between 6 and 24 months. The economic contraction we are facing is potentially unprecedented in modern peace time. This is not a financial crisis; it is a shut-down of the productive economy.

The chances of a rapid, ‘V’ shaped recovery seem slim. The global economy was slowing down prior to the pandemic. Emerging economies face the biggest challenge. With worryingly high levels of public and corporate debt they are in a much worse position than they were before the 2008 financial crisis. When combined with the lowest commodity prices in 40 years, the outlook is bleak for developing economies dependent on exports of primary goods.

Fortunately, due to the nature of this economic downturn, a global food crisis of the likes of 2008 – which saw speculators looking for a safe bet flock to commodities such as food, and a doubling of prices for many staples led to widespread food insecurity – seems unlikely. Nonetheless for the hundreds of millions living in absolute precarity, the material effects of the oncoming economic downturn will seriously undermine their ability to access food.

Thus, while some (the author included) may be fantasizing about the collapse of global capitalism, the structures of dependency created through trade liberalisation and globalisation in the creation of the corporate food regime have left developing countries and the world’s poor the most vulnerable to systemic crises.

The hope is that cash-transfer and food distribution programmes could mitigate the worst effects of food insecurity. For example, India has announced a $22 Billion programme, which includes the distribution of rations of grains and lentils to 800 million people and cash transfers to 200 million vulnerable women and elderly people. However India is one of the world’s fastest growing economies – the risk is that more vulnerable countries will struggle to even maintain existing welfare programmes. The FAO has warned that in Latin America and the Caribbean the closure of schools and their feeding programmes could push 10 million children into hunger.

Developing economies lacking monetary sovereignty cannot push through enormous stimulus packages to insulate their populations from the worst of this crisis. To prepare their public health systems and dampen the effects of the global recession, poor countries will be forced to borrow ‘hard’ currencies on international markets or hope for relief from the international financial institutions like the IMF and World Bank. So, whilst the German treasury is setting up a €500 billion euro fund to re-capitalize German corporations, the UN, World Bank, and IMF are setting up funds with a value of one, 12 and 50 billion dollars respectively, for the whole world!

When material solidarity for developing countries is inadequate at the best of times, how generous will donor countries be now that they face the worst economic crisis in recent history? The fear is that some may seek opportunity in crisis. David Malpass, the Trump-appointed president of the World Bank has already stated in a meeting of G20 finance ministers that

Countries will need to implement structural reforms… countries that have excessive regulations, subsidies, licensing regimes, trade protection or litigiousness as obstacles, we will work with them to foster markets, choice and faster growth prospects during the recovery.

We cannot risk global south governments once again being asked to exchange their sovereignty for short-term relief.

Taking back control of our food system:

Today we need a structural adjustment of a different kind. As the world economy and global trade slow down, supply chains are simplified and states begin to intervene more in markets we must take the opportunity to begin a managed transition to a more resilient and just food system, rooted in the principles of agroecology and food sovereignty.

Agroecology combines traditional and indigenous knowledge with agronomic science to find optimal solutions for local environments. It encourages natural synergies between plants and animals and reduces dependencies on expensive and toxic inputs by prioritising natural solutions to pest control, fertilisation and soil regeneration. Small farms employing methods suited and designed to work with rather than against their local ecology have been shown to be able to produce higher agricultural output per unit area than industrial farms, at much lower economic and environmental costs. We do not need industrial agriculture to feed the world.

Food sovereignty goes beyond the idea of food security, it is a cultural and material principle which centres the need for a restorative agriculture that provides dignified livelihoods. For decades the international peasants’ movement La Via Campesina has fought for the right to food sovereignty, defined as the right for peasants

“to define their own agriculture and food policies, to protect and regulate domestic agricultural production and trade in order to achieve sustainable development objectives, to determine the extent to which they want to be self reliant…”

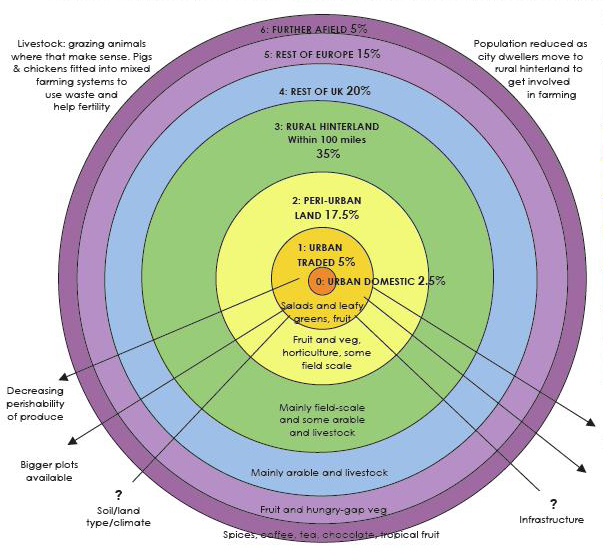

This is not a reactionary anti-globalist agenda, it is an alter-globalist vision. Highly integrated, export-oriented monoculture agriculture needs to be replaced by an international network of diverse localised agricultural economies, engaged in trade but prioritising domestic production and shorter supply chains which retain value within communities.

A handful of states around the world, such as Bolivia, Nepal and Senegal have constitutionally adopted the principle of food sovereignty as a formal right but victories have been more discursive than substantive and it has yet to gain the material policy support requisite for our food systems to be transformed.

To shift the balance of power in our food system subsidies and tax breaks for multinational agri-business will need to be replaced with funding and policies supporting small producers such as minimum price guarantees. The global institutions that regulate and steer global agricultural trade will need to be transformed or replaced with new bodies that prioritise building a food system that respects human rights above the right to profit. On the ground, decentralising the food system will require extensive redistributive land reform – breaking up export-oriented corporate monocultures and replacing them with small and diversified farms.

The corporate food regime is an incredibly successful political project, fought for tooth and nail over several decades to bring about a revolution in the way in which people around the world relate to food. As the coronavirus crisis reveals the deep injustice of that system and we enter increasingly uncertain times we need to build a transformative vision for a radically different project, one that fosters resilience and ensures human dignity.